We're loading the complete profile of this person of interest including their biography, achievements, and contributions.

Judge of the Supreme Court of Kenya

Public Views

Experience

Documented career positions

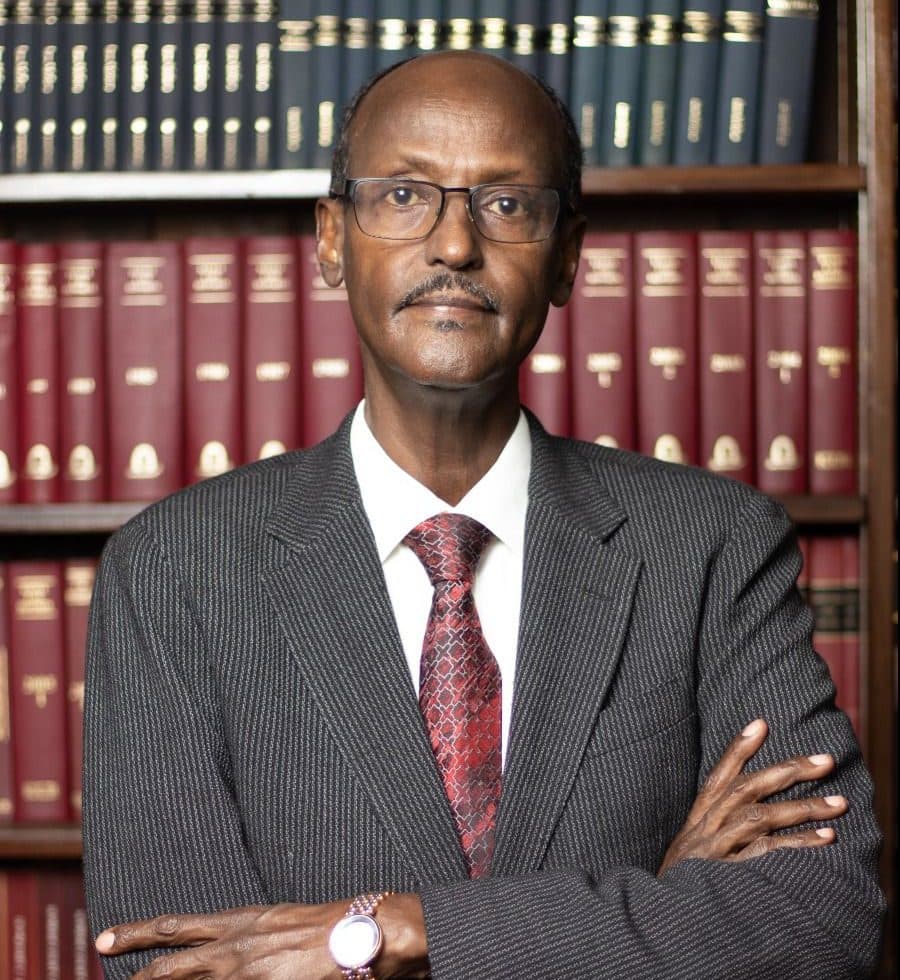

Justice Mohammed Khadhar Ibrahim (1 January 1956 – deceased) was a distinguished Kenyan jurist and a Judge of the Supreme Court of Kenya. He was appointed to the apex court as part of its inaugural bench on 16 June 2011 following an open and competitive process. A pioneer from the Kenyan Somali community, Justice Ibrahim studied law at the University of Nairobi, joined Waruhiu & Muite Advocates in 1982, and was admitted to the Roll of Advocates in January 1983—widely recognised as the first Kenyan Somali to be admitted to the Bar. Over the next two decades, he built a formidable reputation as a leading commercial and constitutional lawyer, with extensive practice in banking, company, property, and insurance law, alongside high-profile public-interest litigation. Beyond legal practice, Justice Ibrahim was deeply involved in Kenya’s human-rights and pro-democracy struggles. In the late 1980s and early 1990s, he provided legal support to reformist politicians and activists, was detained without trial in 1990 for his role in the second liberation movement, and became a prominent advocate for minority and marginalised communities—particularly Kenyan Somalis. He is especially remembered for challenging the discriminatory “pink card” regime that relegated Kenyan Somalis to second-class citizenship. He was appointed a Judge of the High Court in May 2003, serving in Nairobi (Civil, Commercial, and Constitutional Divisions), Eldoret, and Mombasa. Upon his elevation to the Supreme Court, Justice Ibrahim sat on several landmark constitutional and presidential-election cases. He also served as Chair of the Judiciary Committee on Elections and represented the Supreme Court on the Judicial Service Commission (JSC). Justice Mohammed Khadhar Ibrahim is remembered as a trailblazer, reformer, and principled jurist whose legacy profoundly shaped Kenya’s constitutional jurisprudence and the struggle for equality, justice, and the rule of law.

Inaugural Supreme Court Justice and senior jurist: Appointed to the first Supreme Court bench under the 2010 Constitution in June 2011, he is one of the longest-serving justices and among the court’s senior members, having participated in foundational presidential-election petitions and constitutional decisions that helped define the court’s authority.

Champion of minority and citizenship rights: As both advocate and judge, Ibrahim has been cited for his sustained defence of minority groups, especially Kenyan Somalis—challenging discriminatory identification policies and pushing for recognition of full citizenship rights, an aspect highlighted in Supreme Court commemorative narratives.

2012 vetting board finding of “unfit” and subsequent clearance: Following the 2010 Constitution, the Judges and Magistrates Vetting Board initially found Justice Ibrahim “unfit” to continue serving, citing a substantial backlog of delayed rulings from his period as a High Court judge. A later High Court-driven process led to his re-vetting and eventual clearance to continue serving, and he remained on the Supreme Court bench.

Petitions seeking removal of Supreme Court judges: Alongside the Chief Justice and his colleagues, Ibrahim has been named in multiple petitions filed at the JSC and challenged in the High Court, alleging misconduct or incompetence by the entire Supreme Court bench—particularly in the wake of contentious electoral and constitutional decisions. As of early 2025, key High Court rulings have stayed or limited JSC proceedings while broader constitutional questions about process and jurisdiction are litigated; no final adverse finding or removal order against him has been issued.

News articles featuring Mohammed Ibrahim

Leadership in judicial governance and elections: He serves as Chairperson of the Judiciary Committee on Elections (JCE), overseeing the Judiciary’s preparedness and engagement on electoral disputes, and since 2022 has represented the Supreme Court on the Judicial Service Commission, sitting on key committees on finance, administration of justice, learning and development.

Contribution to Kenya’s second liberation and human-rights movement: His detention without trial in 1990 for providing legal aid to pro-democracy figures, and his roles in organisations such as Kituo cha Sheria, LEAD and Mwangaza Trust, have earned him recognition as part of the legal vanguard that pushed for multiparty democracy and a rights-based constitutional order.

Criticism over delayed judgments: Even after his re-vetting, public and academic commentary has occasionally revisited earlier concerns about timeliness of judgment delivery, using his 2012 vetting experience as a case study in judicial accountability. These critiques focus on systemic issues—heavy caseloads, limited resources and structural bottlenecks—rather than on new, specific delay findings against him as a Supreme Court judge.

Political heat around presidential-election decisions: His participation in divisive presidential-election petitions (including 2013 and subsequent cycles) has inevitably drawn partisan criticism from losing camps, who at different times have attacked the entire bench for either “judicial activism” or “judicial capture”. These disputes are political and rhetorical; there is no record of a disciplinary body establishing that Justice Ibrahim personally engaged in misconduct in relation to these decisions.