We're loading the full news article for you. This includes the article content, images, author information, and related articles.

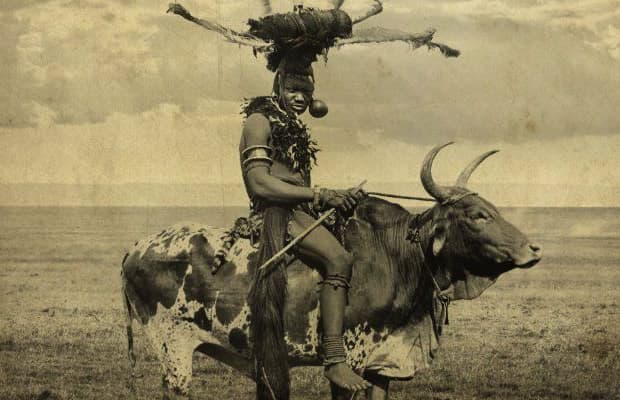

In Luo tradition, the return of dowry formalises divorce, yet leaving one cow and a goat signifies a lasting connection, preventing complete severance between families. This enduring custom navigates the complexities of separation

Among the Luo, one of Kenya's largest ethnic groups, the dissolution of a customary marriage is a process as ritualised as its formation. While the return of dowry, known as 'keny', signifies the end of a union, the deliberate retention of one cow and one goat by the bride's family is a crucial, symbolic act that maintains a sliver of connection, according to Luo elders. This practice underscores a cultural understanding that even in separation, familial ties are not entirely erased.

The process of a Luo customary marriage traditionally involves two main stages: 'Ayie', where the groom's family presents gifts to the bride's mother to gain her acceptance, and 'Nyombo', the formal dowry payment, typically in cattle, to the bride's father. This exchange solidifies the bond between the two families. Consequently, a divorce requires a formal reversal of this process. According to Magai Jonyo, a representative of the Luo Council of Elders from Karachuonyo, a man is entitled to reclaim the cattle paid as dowry if the marriage dissolves. This reclamation is not merely a financial transaction but a powerful symbol that the connection between the two families has been severed.

The core of this tradition lies in what is left behind. The single cow, referred to as "Dher Ot," which translates to "the cow of the house," remains at the woman's paternal home as a permanent acknowledgment of the union that once was. It serves as a testament that the woman was once honourably married and is not being returned in disgrace. More importantly, it signifies that the children born from the marriage rightfully belong to the husband's lineage. Should the husband accept a full return of the dowry, he would forfeit all paternal rights to the children, and their lineage would revert to their mother's family.

The goat, known as "Diel Ot," has a distinct and equally vital purpose. It represents the enduring possibility of reconciliation. Its presence signifies that the channels of communication between the two families remain open. Should the couple decide to reunite in the future, the path is not entirely closed. This tradition provides a cultural safety net, allowing for the potential mending of broken relationships without the shame or complexity of renegotiating a completely new marriage.

The return of dowry is not automatic and is adjudicated by elders from both families. It is typically initiated under specific circumstances. A woman can request her family to return the dowry if she is unequivocally done with the marriage and perhaps wishes to remarry. Alternatively, if a wife deserts her marital home for good, the husband's family can initiate the process to retrieve the livestock. However, if the man's family is deemed to be at fault for the separation, they may not receive the full dowry back. The elders' council plays a critical role in these deliberations, ensuring that the dissolution is handled with fairness and adherence to custom.

Under Luo customary law, a marriage is considered legally binding until the dowry is formally returned. This has significant implications, particularly for women. A woman cannot remarry or have her new partner pay dowry to her family if the dowry from a previous marriage has not been returned. Furthermore, any children she bears in a subsequent relationship are, by custom, considered to belong to the first husband until the dowry is settled.

While these customs have been practiced for generations, their application in contemporary Kenya is evolving. The blend of traditional, religious, and civil marriages has led to a decline in the strict observance of some of these practices. However, elders maintain their importance in preserving Luo cultural identity. The Kenyan legal system recognizes customary marriages and their dissolution, provided they do not conflict with the constitution. High Court rulings have, in some instances, upheld the principles of customary law, such as in burial disputes where the payment of dowry was a determining factor in deciding spousal rights. Yet, these traditions also face scrutiny regarding gender equality and individual rights in a modern legal framework. The enduring practice of leaving one cow and one goat highlights the nuanced Luo approach to marriage and divorce—a system that provides for definitive separation while acknowledging the lasting social and familial bonds that a marriage creates.

Keep the conversation in one place—threads here stay linked to the story and in the forums.

Sign in to start a discussion

Start a conversation about this story and keep it linked here.

Other hot threads

E-sports and Gaming Community in Kenya

Active 9 months ago

The Role of Technology in Modern Agriculture (AgriTech)

Active 9 months ago

Popular Recreational Activities Across Counties

Active 9 months ago

Investing in Youth Sports Development Programs

Active 9 months ago