We're loading the full news article for you. This includes the article content, images, author information, and related articles.

**Health officials are battling a surge in severe animal-to-human infections in Marsabit County, forcing a difficult conversation about the cherished, but dangerous, pastoralist tradition of consuming raw milk and meat.**

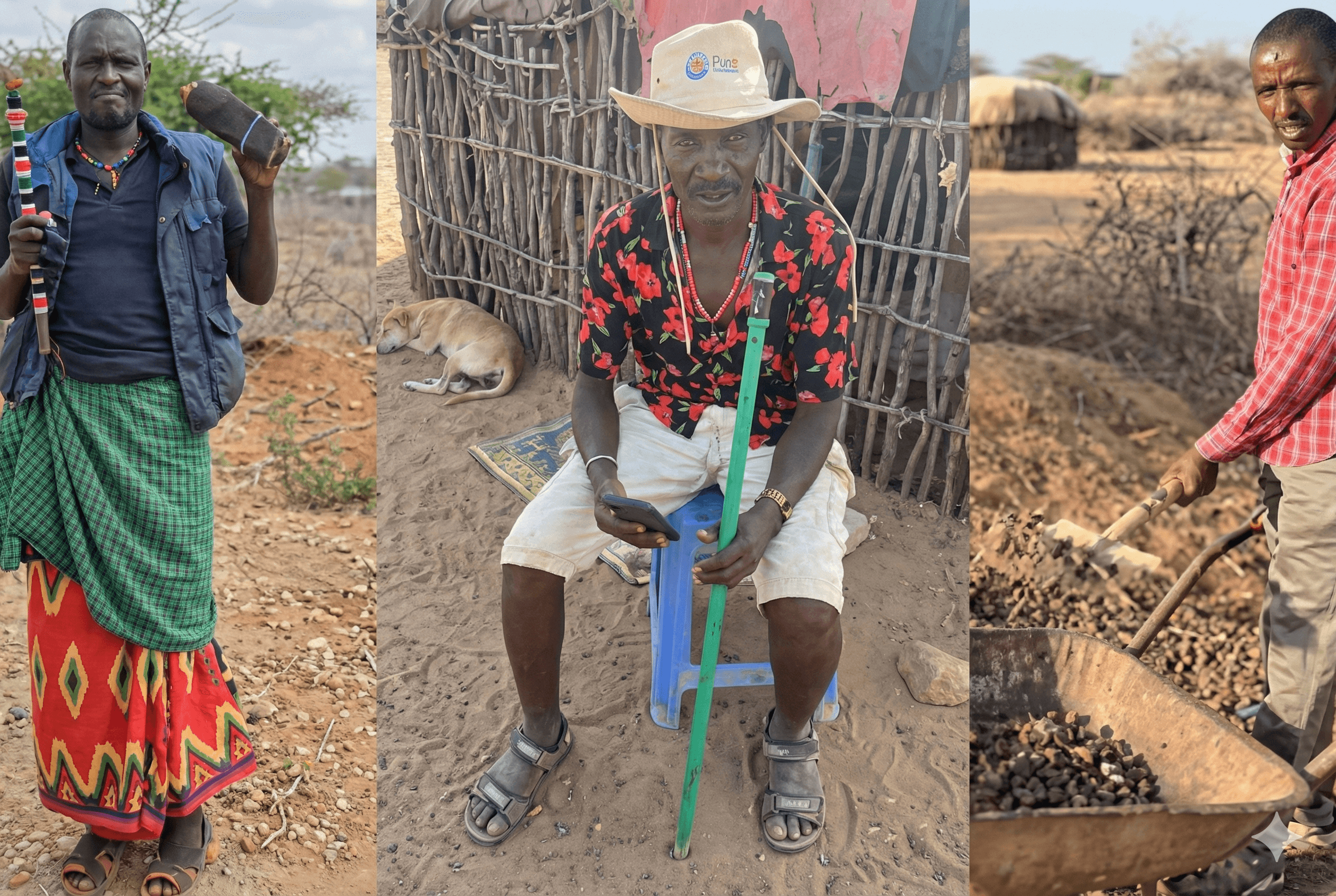

A quiet public health crisis is unfolding across the arid plains of Marsabit, not from a new virus, but from a deeply ingrained cultural practice. The tradition of consuming raw milk, blood, and meat is now at the centre of a spike in zoonotic diseases, particularly the debilitating bacterial infection, brucellosis.

This is not just a health issue; it is an economic catastrophe for a community whose very existence is woven into the health of its livestock. With recent studies showing a staggering 51% of animals in Marsabit are infected with brucellosis and a human sero-prevalence (or evidence of exposure) as high as 44%, county and national health officials have intensified a campaign to change behaviours that are centuries old.

For generations, pastoralist communities like the Borana, Gabbra, and Rendille have relied on their animals for sustenance, with raw animal products forming a core part of their diet. This practice, however, comes with a hidden cost. Brucellosis in humans mirrors the symptoms of malaria and typhoid—prolonged fever, joint pain, and chronic fatigue—often leading to misdiagnosis and prolonged suffering. For livestock, it causes abortions and infertility, directly impacting a family's wealth and food security.

"My wife has suffered from brucellosis. She used to feel pain in her joints; she could not walk," Daudi Dokhole, a community health promoter from Laisamis, shared with reporters. His story is a common one, where the connection between sick animals and sick family members was not understood until a formal diagnosis was made, a process that for many is out of reach.

In response, a multi-pronged strategy is being rolled out. The Kenyan government, through its One Health Strategic Plan, is pushing for a more integrated approach to diseases that cross the animal-human divide. Recently, the Ministry of Health launched new national guidelines for Human Brucellosis Testing and a Rift Valley Fever Contingency Plan to standardize diagnostics and improve early detection.

On the ground in Marsabit, the focus is on direct community engagement. Health workers are training local residents on safer food handling and animal husbandry. The key public health directives include:

The economic toll of these diseases is immense. One study estimated that brucellosis in cattle alone causes an economic loss of $237.5 million (approx. KES 30.8 billion) annually in Kenya, primarily through lost production in pastoralist systems. This stark figure underscores the urgency of the intervention, framing it not just as a health measure, but as a vital effort to protect livelihoods.

The challenge is immense, requiring a delicate balance between respecting cultural heritage and ensuring public safety. Yet, there are signs of change. Community disease reporters are now using mobile tools to track livestock health, and individuals are beginning to adopt new habits. "I used to drink raw blood for many years but stopped, and I am now campaigning in my community so that we stop this culture," noted one resident, highlighting a slow but crucial shift in mindset.

Keep the conversation in one place—threads here stay linked to the story and in the forums.

Sign in to start a discussion

Start a conversation about this story and keep it linked here.

Other hot threads

E-sports and Gaming Community in Kenya

Active 9 months ago

The Role of Technology in Modern Agriculture (AgriTech)

Active 9 months ago

Popular Recreational Activities Across Counties

Active 9 months ago

Investing in Youth Sports Development Programs

Active 9 months ago