We're loading the full news article for you. This includes the article content, images, author information, and related articles.

Recent amendments to Kenya's cybercrime law focus heavily on content regulation and harsh penalties for online speech, sparking fears of censorship while potentially overlooking larger, more sophisticated threats to the nation's critical infrastructure and burgeoning digital economy.

NAIROBI - On Friday, October 31, 2025 (EAT), Kenya finds itself at a critical juncture in its digital evolution. The recent assent to the Computer Misuse and Cybercrimes (Amendment) Act, 2024, has ignited a fierce national debate, pitting state security imperatives against fundamental constitutional freedoms. While the government champions the law as a necessary tool to combat a surge in online fraud, harassment, and the spread of extremist content, a broad coalition of civil society, legal experts, and digital rights advocates warns that its vague language and expanded state powers risk chilling free expression and targeting dissent.

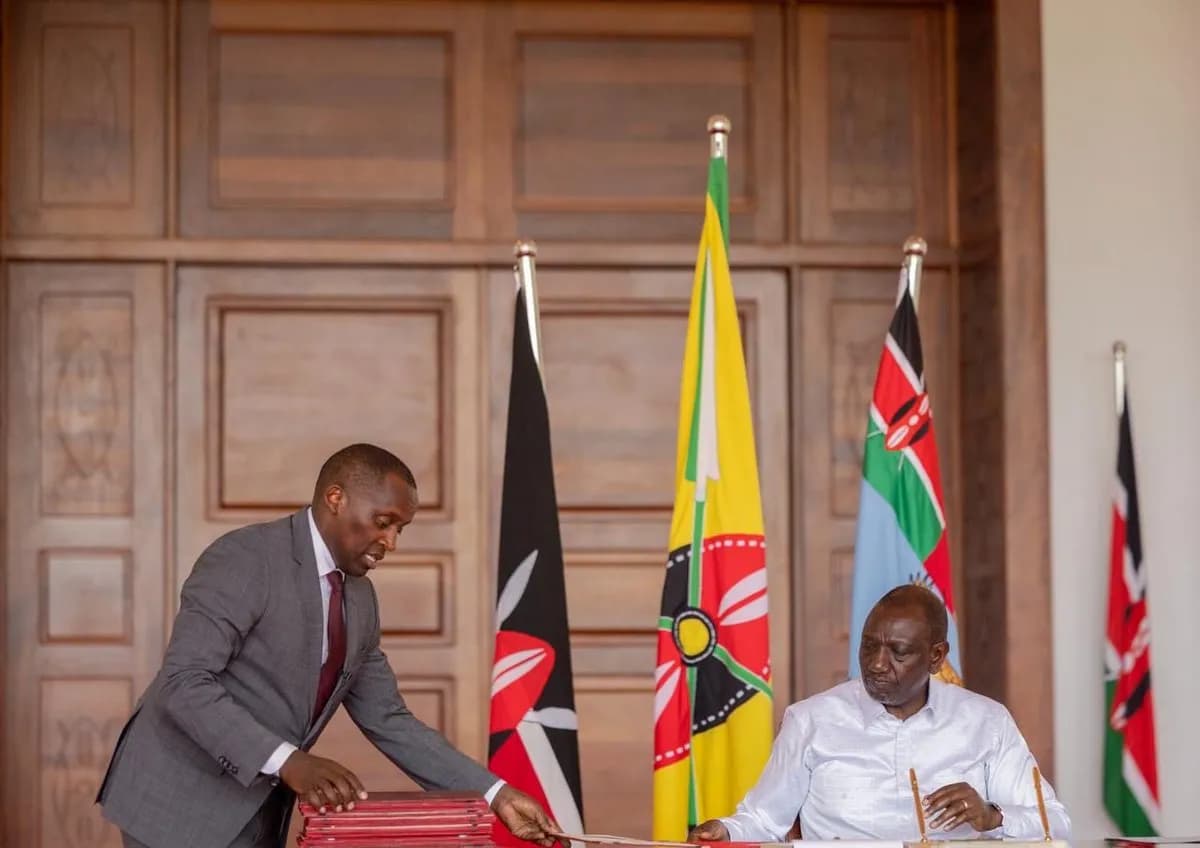

The amended law, which builds on the 2018 Act, introduces stiffer penalties for cyber harassment, criminalizes the unauthorized use of SIM cards and phishing via phone calls, and grants the National Computer and Cybercrimes Coordination Committee (NC4) sweeping authority to order the blocking of websites or applications deemed to promote terrorism, child pornography, or “extreme religious and cultic practices.” President William Ruto, speaking in Laikipia County on October 23, 2025, defended the legislation, stating, “Our young people are being harassed; they are being terrorised on social media. We must stop that.” However, critics argue that provisions criminalizing content that is “likely to cause a person to commit suicide” or spreading “false, misleading, or fictitious data” are dangerously ambiguous and could be weaponized against journalists and government critics, a concern with historical precedent in Kenya.

The government's legislative push is not without cause. Kenya, a hub for technology and mobile finance in East Africa, faces a relentless barrage of cyberattacks. The Communications Authority of Kenya (CA) reported a staggering 2.54 billion cyber threat incidents between January and March 2025, a 201.7% increase from the previous quarter. Between April and June 2025, the National KE-CIRT/CC detected over 4.5 billion threat events. These attacks have significant economic consequences; in 2023 alone, Kenya lost an estimated $83 million (approximately KSh 12.3 billion) to cybercrime.

Recent high-profile incidents underscore the nation's vulnerability. In January 2025, Kenya's Business Registration Service suffered a major data breach, exposing the sensitive information of prominent figures, including President Ruto. A massive cyberattack in July 2023, attributed to the pro-Russian hacking group Anonymous Sudan, crippled over 5,000 government e-services, disrupting everything from passport applications to mobile money transactions. Furthermore, a 2025 report from SOCRadar highlighted that Kenya's public administration, finance, and information services sectors account for over 43% of all cyber incidents, with ransomware attacks increasingly targeting the manufacturing sector.

While the CMCA amendment addresses tangible issues like SIM-swap fraud and online harassment, analysts argue it misses the bigger picture by focusing disproportionately on policing content rather than building robust defenses against systemic threats. The primary concern is the growing threat to Kenya's Critical National Infrastructure (CNI), defined under the Act as systems essential to the health, safety, and economic well-being of Kenyans. Between July 2022 and June 2023, the National KE-CIRT/CC detected over 855 million threats aimed at this critical infrastructure.

Experts point to a strategic deficit. The law's emphasis on punitive measures for individual speech does little to counter state-sponsored hacking groups or sophisticated ransomware gangs like LockBit and Cl0p that target key economic sectors. There is a critical shortage of cybersecurity experts in the country, and many employees in critical sectors lack adequate awareness and training, creating vulnerabilities that legislation alone cannot fix. The law is also seen as reactive, struggling to keep pace with threats posed by emerging technologies like Artificial Intelligence, which are increasingly used by criminals.

The debate over the cybercrime law reflects a global challenge: how to regulate the digital space without undermining democratic principles. While the government's stated intention is to align with international frameworks like the Budapest Convention, critics argue the Kenyan law's implementation deviates from international standards by failing to adequately protect digital rights. Comparative analyses show that while nations like Rwanda also have strong cybersecurity policies, Kenya's framework is particularly criticized for vague provisions that can be used to suppress dissent.

As legal challenges against the Act proceed in the High Court, the path forward requires a multi-faceted approach. This includes not only refining the legislation through genuine public participation to protect free expression but also shifting focus and resources towards proactive cybersecurity measures. Strengthening public-private partnerships, investing in capacity building and technical skills, and fostering a national culture of cybersecurity awareness are paramount. Without a strategic pivot towards defending against large-scale economic and infrastructural threats, Kenya's digital superhighway risks being policed by a law that is adept at silencing critics but ill-equipped to stop the catastrophic attacks looming on the horizon. FURTHER INVESTIGATION REQUIRED.

Keep the conversation in one place—threads here stay linked to the story and in the forums.

Sign in to start a discussion

Start a conversation about this story and keep it linked here.

Other hot threads

E-sports and Gaming Community in Kenya

Active 9 months ago

The Role of Technology in Modern Agriculture (AgriTech)

Active 9 months ago

Popular Recreational Activities Across Counties

Active 9 months ago

Investing in Youth Sports Development Programs

Active 9 months ago