We're loading the full news article for you. This includes the article content, images, author information, and related articles.

A High Court ruling has temporarily halted controversial new powers that grant the state sweeping authority to block websites and police online speech, escalating a national battle between digital rights and state control.

NAIROBI - Key sections of Kenya's contentious Computer Misuse and Cybercrimes (Amendment) Act, 2025, have been suspended by the High Court, following a wave of legal challenges from human rights groups and activists. The temporary halt, issued by Justice Lawrence Mugambi on Wednesday, October 22, 2025, puts a brake on the government's expanded powers to regulate the digital space, which critics warn could be used to suppress dissent and curtail freedom of expression.

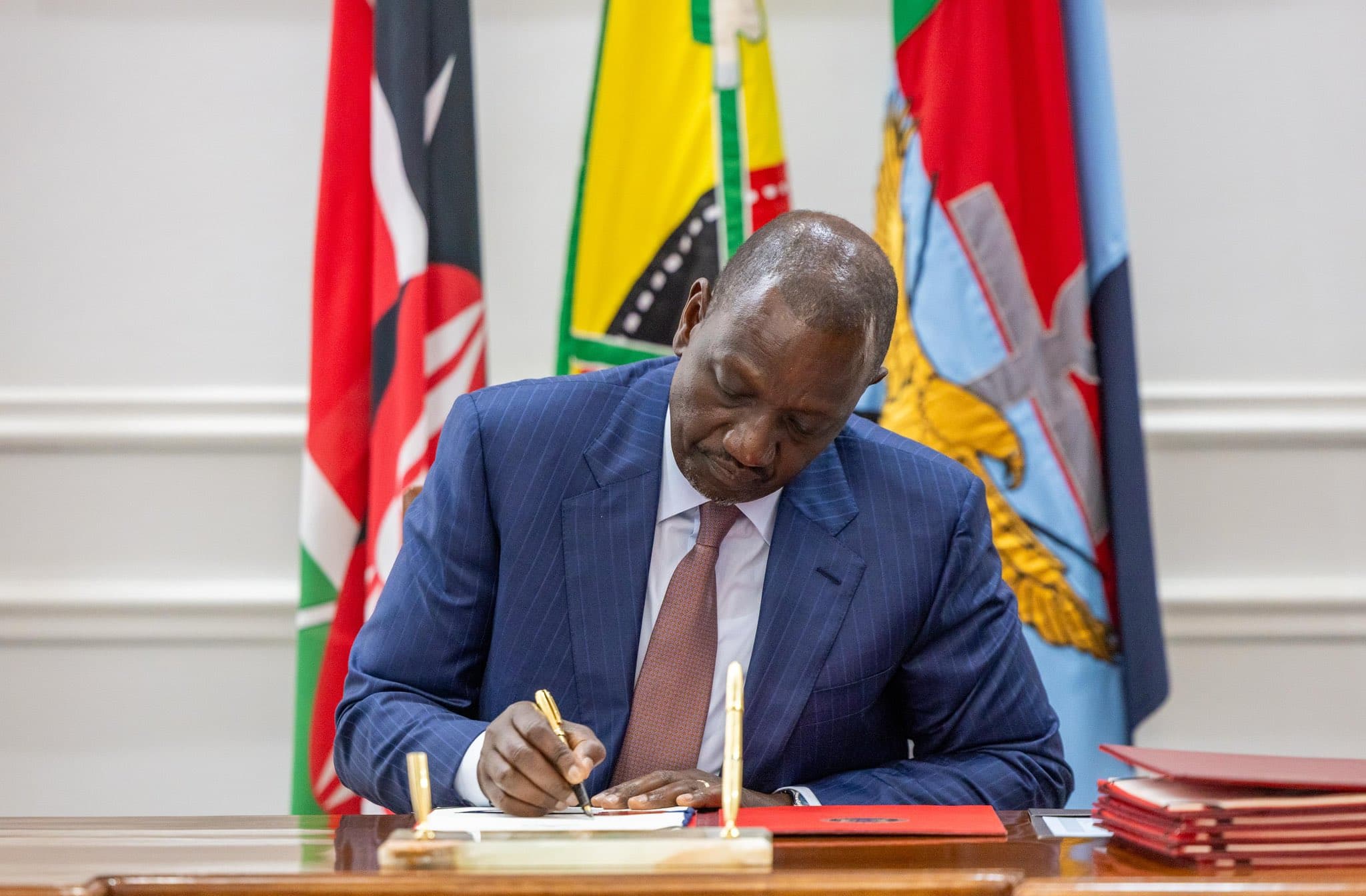

The amended law, signed by President William Ruto on Wednesday, October 15, 2025, introduced significant changes to the original 2018 Act. The government has defended the legislation as a necessary tool to combat escalating digital threats. According to Government Spokesperson Isaac Mwaura, the amendments strengthen Kenya's ability to fight child pornography, online extremism, terrorism propaganda, cyber-harassment, identity theft, and financial fraud.

However, the changes have sparked widespread alarm among civil society organizations, legal experts, and the Kenyan public. At the heart of the controversy are provisions granting the National Computer and Cybercrimes Coordination Committee (NC4), a body largely composed of security officials, the power to order the blocking of websites and applications without prior judicial oversight. The law targets platforms deemed to promote illegal activities, child pornography, terrorism, or the vaguely defined "extreme religious and cultic practices."

The original Computer Misuse and Cybercrimes Act of 2018 was contentious from its inception. Enacted to create a legal framework against digital crime, its provisions on spreading "false" or "misleading" information were immediately flagged by rights groups like ARTICLE 19 as a threat to free expression. The Bloggers Association of Kenya (BAKE) filed a petition that led to the suspension of 26 sections of the Act on May 30, 2018. However, the High Court lifted this suspension in a ruling on February 20, 2020, bringing the entire law into force.

Critics argue the 2025 amendments dangerously amplify the most problematic aspects of the original law. The definition of cyber harassment has been broadened to include communication that is "likely to cause" a person to commit suicide, a clause that opponents say is subjective and open to abuse. Penalties remain severe, with convictions for cyber harassment carrying fines of up to KSh 20 million, a prison term of up to ten years, or both.

The latest legal battle saw musician and activist Reuben Kigame and the Kenya Human Rights Commission (KHRC) successfully petition the High Court for a temporary suspension of the amended Section 27, among others. Their petition argues that the law is unconstitutional, infringing on the rights to privacy, freedom of expression, and access to information. As of Wednesday, November 5, 2025, at least six petitions challenging the law have been filed.

The process of the bill's passage has also drawn sharp criticism. Kiambu Senator Karungo wa Thang'wa accused President Ruto of a "gross violation of the Constitution" by signing the bill into law without it ever being brought before the Senate for consideration, as required for legislation affecting county governments. This procedural oversight is part of a broader concern that the executive is fast-tracking legislation without adequate public participation or parliamentary oversight, a trend some have dubbed "sneaky bills."

The debate over the Cybercrimes Act reflects a deeper tension in Kenya's democracy: the balance between national security and fundamental freedoms. Proponents, including Dagoretti North MP Beatrice Elachi, argue the law aligns Kenya with international standards for combating digital child abuse. The amendments also introduce specific offenses for emerging crimes like SIM-swap fraud and expand the definition of phishing to include fraudulent phone calls ('vishing'), which have been acknowledged as positive steps.

However, rights advocates maintain that the law's vague language could be weaponized to silence government critics, journalists, and activists, creating a chilling effect on online discourse. Organizations such as ICJ Kenya and ForumCiv have warned that the law could reverse years of progress in media freedom. With the High Court's intervention, the future of digital expression in Kenya now hangs in the balance, pending a full constitutional review of a law that could redefine the boundaries of speech in one of Africa's most vibrant digital landscapes.

Keep the conversation in one place—threads here stay linked to the story and in the forums.

Other hot threads

E-sports and Gaming Community in Kenya

Active 8 months ago

The Role of Technology in Modern Agriculture (AgriTech)

Active 8 months ago

Popular Recreational Activities Across Counties

Active 8 months ago

Investing in Youth Sports Development Programs

Active 8 months ago

Key figures and persons of interest featured in this article