We're loading the full news article for you. This includes the article content, images, author information, and related articles.

Astronomers using the James Webb Space Telescope have solved a long-standing mystery of planetary formation, discovering a "cosmic highway" that transports life-essential crystals from stars to the outer solar system.

In a groundbreaking discovery that reshapes our understanding of how solar systems—including our own—are built, astronomers have found the first direct evidence of common crystals being forged in the fiery heart of a young star and hurled into deep space.

The findings, published today in the prestigious journal Nature, solve a decades-old cosmic mystery: how do crystalline silicates, which require searing heat to form, end up in comets that dwell in the freezing outer reaches of space? The answer, provided by NASA’s James Webb Space Telescope (JWST), reveals a turbulent "cosmic highway" that transports these minerals from a star’s molten core to its icy halo.

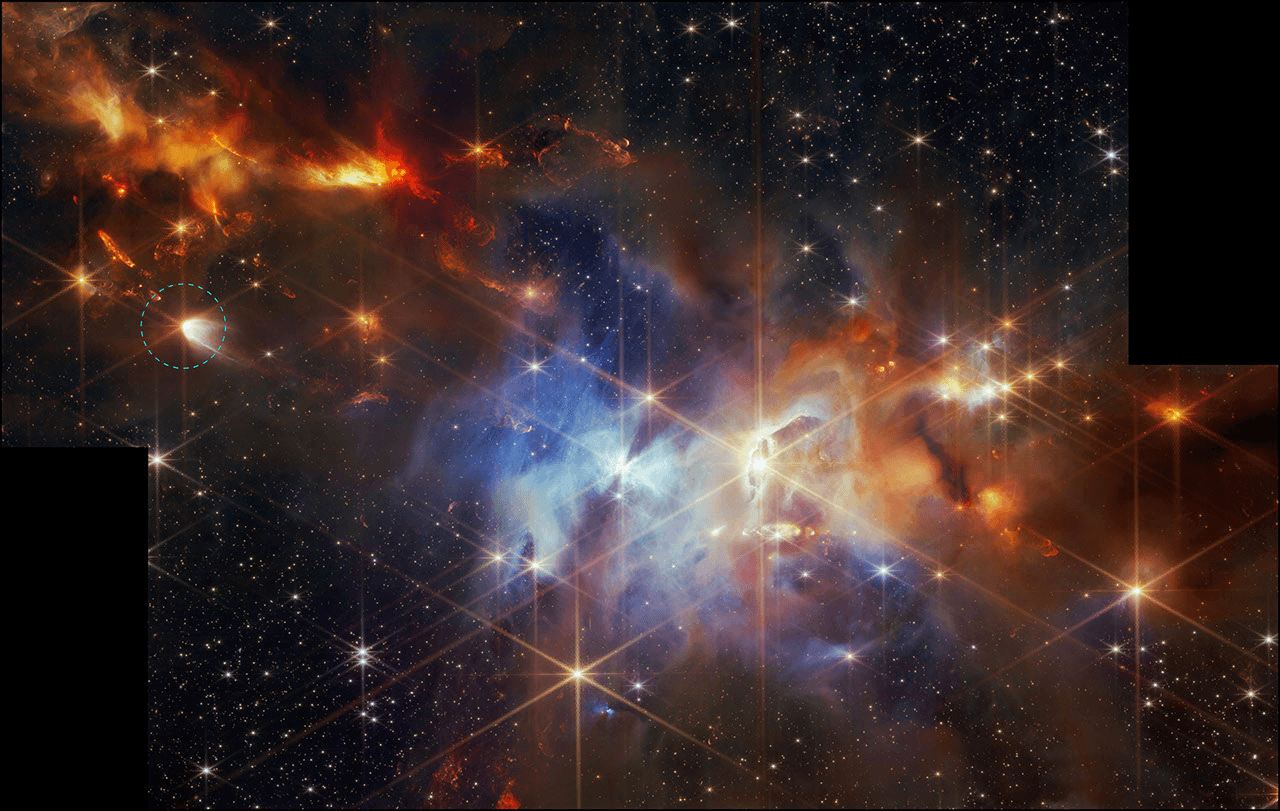

The research team, led by Professor Jeong-Eun Lee of Seoul National University, trained the Webb telescope’s powerful Mid-Infrared Instrument (MIRI) on a protostar known as EC 53. Located approximately 1,300 light-years away in the Serpens Nebula, EC 53 is a stellar infant, still wrapped in a thick blanket of gas and dust.

For the first time, scientists observed the star during a violent "outburst" phase. The data showed that crystalline silicates—minerals like forsterite and enstatite, which are abundant in Earth’s rocks—were being forged in the massive heat of the star’s inner disk, where temperatures soar above 600 degrees Celsius (1,100 degrees Fahrenheit).

More critically, the telescope captured powerful stellar winds catapulting these newly minted crystals outward at high velocities. "It is like a conveyor belt," Professor Lee explained. "The star cooks the dust into crystals, and the winds deliver them to the outer edges where comets are born."

This discovery bridges a gap in the history of our own solar system. Astronomers have long known that comets—the "dirty snowballs" of space—contain these heat-forged crystals. Since comets form in the cryo-freeze of the Kuiper Belt (far beyond Pluto), their composition was a paradox.

"Webb not only showed us exactly which types of silicates are in the dust near the star, but also where they are both before and during a burst," said Doug Johnstone, a co-author from the National Research Council of Canada. The resolution provided by JWST is unprecedented, allowing the team to map dust grains smaller than a single grain of sand across distances of trillions of kilometers.

EC 53 is expected to remain shrouded in its dusty cocoon for another 100,000 years. However, these violent growing pains are setting the stage for a future planetary system—one that might, billions of years from now, look very much like our own.

Keep the conversation in one place—threads here stay linked to the story and in the forums.

Sign in to start a discussion

Start a conversation about this story and keep it linked here.

Other hot threads

E-sports and Gaming Community in Kenya

Active 9 months ago

The Role of Technology in Modern Agriculture (AgriTech)

Active 9 months ago

Popular Recreational Activities Across Counties

Active 9 months ago

Investing in Youth Sports Development Programs

Active 9 months ago