We're loading the full news article for you. This includes the article content, images, author information, and related articles.

A lethal new US anti-drug trafficking strategy in the Pacific sets a controversial precedent for maritime law enforcement, raising critical questions for Kenya’s own approach to combating narcotics and ensuring security in the Indian Ocean.

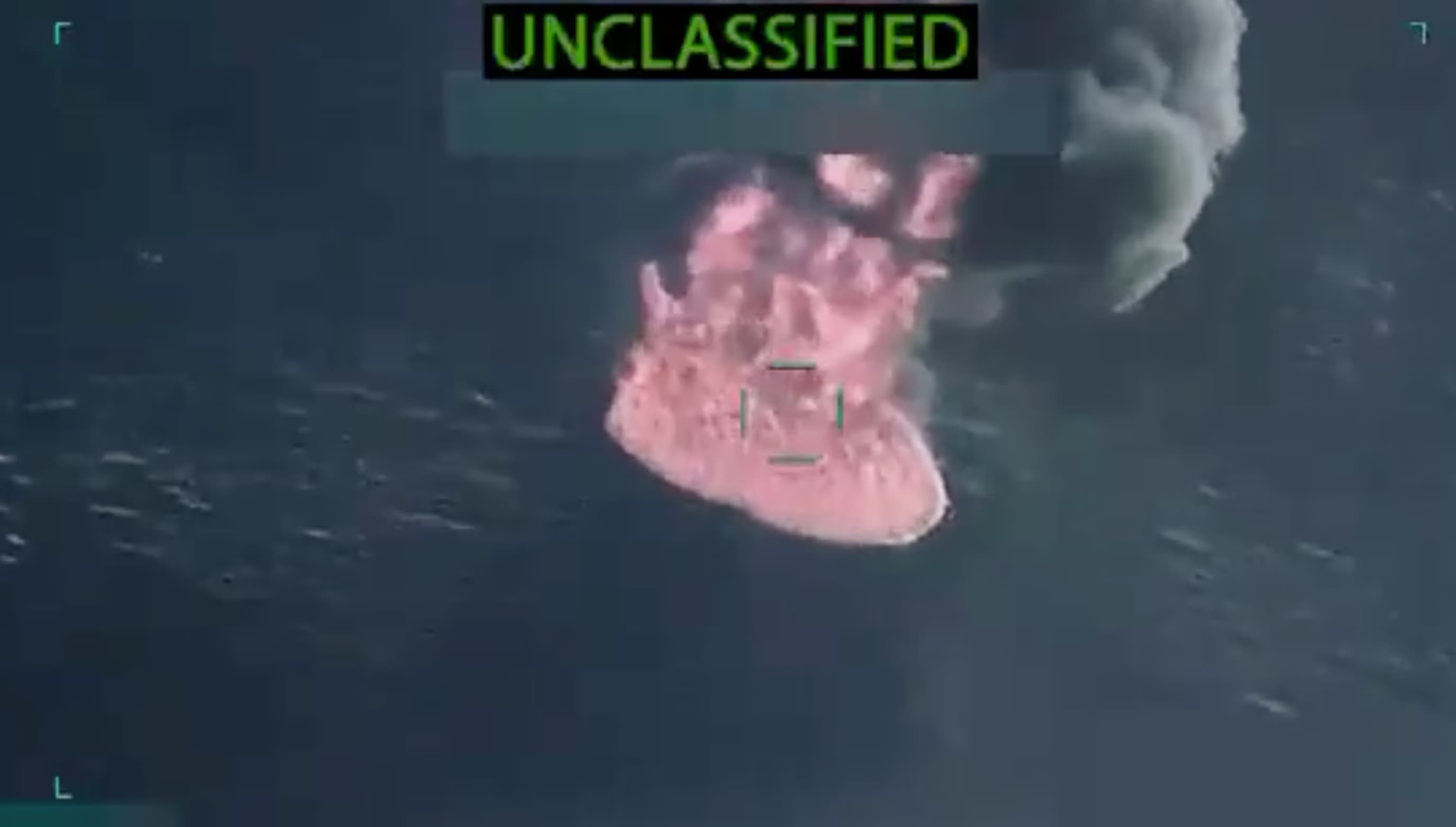

GLOBAL - The United States military has killed 14 people and left one survivor after conducting airstrikes on four vessels in the eastern Pacific Ocean on Monday, October 27, 2025, according to US Secretary of Defense Pete Hegseth. The operation marks the deadliest day in an escalating and controversial campaign against alleged narcotics traffickers that has now expanded from the Caribbean Sea to the Pacific.

In a social media post on Tuesday, October 28, Hegseth stated the strikes were carried out at the direction of President Donald Trump against vessels operated by “Designated Terrorist Organizations.” He asserted that “the four vessels were known by our intelligence apparatus, transiting along known narco-trafficking routes, and carrying narcotics.” The latest attacks bring the total death toll since the campaign began in early September to at least 57 people across 14 destroyed vessels.

Hegseth justified the lethal force by equating the anti-drug mission to the “war on terror,” stating, “These narco-terrorists have killed more Americans than Al-Qaeda, and they will be treated the same. We will track them, we will network them, and then, we will hunt and kill them.” The Trump administration has not publicly provided evidence to substantiate its claims about the vessels' cargo or the identities of those killed.

The strikes, conducted in international waters, have drawn sharp criticism from international law experts and human rights organizations, who argue they may constitute extrajudicial killings. According to the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS), military force on the high seas is severely restricted, generally permitted only in cases of self-defense against an imminent armed attack or for anti-piracy operations. Legal analysts note that drug trafficking, while a serious crime, does not meet the threshold of an “armed attack” that would justify lethal military action under international law. A group of UN human rights experts stated on October 21 that using lethal force in this context without a proper legal basis constitutes “extrajudicial executions.”

The operation has also strained diplomatic ties. The Mexican government, while agreeing to a US request to handle search-and-rescue for the lone survivor, has publicly condemned the attacks. Mexican President Claudia Sheinbaum stated, “we do not agree with these attacks,” and has instructed her foreign affairs secretary to meet with the US ambassador to insist that “all international treaties to be respected.” The Mexican Navy confirmed it was conducting a search operation approximately 640 kilometers southwest of Acapulco.

While geographically distant, the shift in US policy to using lethal military force against suspected criminals in international waters sets a significant global precedent with potential ramifications for Kenya. As a strategic partner of the US in East Africa, particularly on maritime security and counter-terrorism, Kenya faces similar challenges with narcotics trafficking through the Indian Ocean.

Kenya's coastline is a known transit point for narcotics, and its security forces, often in cooperation with international partners like the US and the UN Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC), are actively engaged in maritime interdiction. Just this week, Kenyan authorities announced a major seizure of methamphetamine valued at 8.2 billion shillings from a stateless vessel off the coast, highlighting the scale of the problem. However, Kenya’s approach has been rooted in law enforcement, involving interception, seizure, and prosecution, consistent with international maritime conventions.

The US campaign's framing of traffickers as “narco-terrorists” to be targeted with military force blurs the line between law enforcement and warfare. This could influence future security doctrines globally. For the Western Indian Ocean, a region already contending with piracy, terrorism, and smuggling, such a precedent could be destabilizing. It raises questions about whether other nations might adopt similar tactics, potentially leading to an escalation of violence at sea and undermining the established legal order that governs it.

The US policy stands in stark contrast to the established practice of arrest and prosecution for suspected traffickers. The Washington Office on Latin America (WOLA), a human rights organization, has noted that for decades, US military and Coast Guard personnel have interdicted drug vessels without resorting to lethal force, except in clear cases of self-defense. The current US campaign, therefore, represents a radical departure from these norms, with consequences that could ripple far beyond the Pacific, impacting the global consensus on how nations police the high seas.

Keep the conversation in one place—threads here stay linked to the story and in the forums.

Sign in to start a discussion

Start a conversation about this story and keep it linked here.

Other hot threads

E-sports and Gaming Community in Kenya

Active 9 months ago

The Role of Technology in Modern Agriculture (AgriTech)

Active 9 months ago

Popular Recreational Activities Across Counties

Active 9 months ago

Investing in Youth Sports Development Programs

Active 9 months ago