We're loading the full news article for you. This includes the article content, images, author information, and related articles.

The move aims to revive Kenya's timber sector and create jobs by utilising mature forest resources, but raises significant environmental concerns.

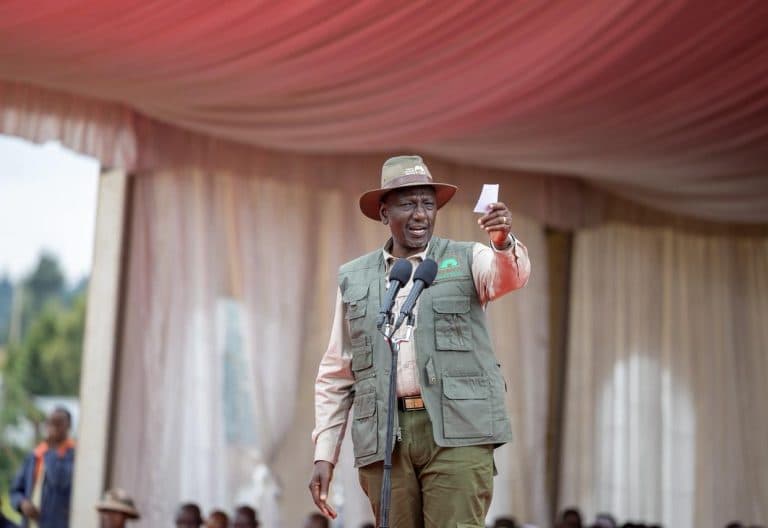

President William Ruto on Monday, October 27, 2025, announced the immediate lifting of a nationwide logging ban and ordered a halt on furniture imports, a dual policy shift aimed at revitalising Kenya's timber industry and creating local employment. The President stated the move is intended to make commercial use of mature and over-mature trees in state plantation forests that would otherwise rot, while simultaneously spurring local manufacturing.

Speaking in Elburgon, Nakuru County, a town historically dependent on the timber trade, President Ruto declared that importing furniture from countries like China must end. "We will use our wood to make furniture," he said, adding, "Furniture in Kenya will use timber from here, and our Kenyan youth will create that furniture." The directive was issued to the Ministry of Trade, led by Cabinet Secretary Lee Kinyanjui, to facilitate the revival of local sawmills and ensure a complete transition to locally manufactured furniture.

The original logging moratorium was imposed in 2018 by the previous administration under President Uhuru Kenyatta, following a public outcry over rampant illegal logging and its detrimental effect on Kenya's water towers, including the vital Mau Forest Complex. The ban's economic impact has been significant. A study by the Kenya Forestry Research Institute (Kefri) indicated that the Kenya Forest Service (KFS) lost over Sh5 billion in revenue and 44,000 jobs were shed in the years following the ban. Towns like Elburgon and Molo, once vibrant hubs of the timber trade, experienced economic decline.

The government's new policy is designed to reverse this trend. President Ruto announced that starting next week, the government will begin selling mature trees from forests across the country to local sawmillers. He is scheduled to meet with regional sawmillers on Tuesday, October 28, to establish clear rules for sustainable harvesting. The locally sourced timber is also expected to support the government's Affordable Housing Programme by providing materials for furniture.

This is not the first attempt by the Ruto administration to repeal the ban. A similar lifting in June 2023 was blocked by the High Court two months later after a petition by the Law Society of Kenya (LSK) cited a lack of public participation. It remains to be seen if this latest directive will face legal challenges.

While championing the economic benefits, President Ruto has cautioned that the lifting of the ban is not a license for uncontrolled forest destruction. The directive strictly applies to the harvesting of mature trees in commercial plantations, not indigenous forests. "The lifting of the logging ban does not mean that we destroy our forests. It means we will harvest trees responsibly, replant them, and ensure our forests remain sustainable," President Ruto stated.

The announcement was made concurrently with the launch of the Mau Forest Complex Integrated Conservation and Livelihood Improvement Programme, where the President participated in a tree-planting exercise. The government aims to restore 33,000 hectares of the Mau Complex and reiterated its commitment to planting 15 billion trees nationwide within ten years.

Despite these assurances, environmental groups have previously expressed alarm. When the ban was first lifted in 2023, critics warned the move could derail efforts to increase Kenya's tree cover from its current 8.8 percent. The Kenya Forest Service (KFS) has previously stated it has a plan to manage harvesting by limiting it to a maximum of 5,000 hectares per year and automating licensing to ensure accountability. The core of the debate remains balancing the immediate economic needs of timber-dependent communities with the long-term imperative of conserving Kenya's critical forest ecosystems.

The ban on furniture imports is an extension of a 2020 policy by the Kenyatta administration that blocked state agencies from importing furniture. This new, broader ban will likely impact the availability and cost of furniture for the Kenyan public in the short term. The Kenya Association of Manufacturers (KAM) warned in 2020 that an influx of cheaper imported furniture was undermining local production, which was growing at only 7 percent annually compared to the 22 percent growth in imports. The ban, coupled with the availability of local timber, is intended to make the domestic industry more competitive. The success of this protectionist policy will depend on the local industry's capacity to scale up production to meet national demand for quality and affordable furniture.

Keep the conversation in one place—threads here stay linked to the story and in the forums.

Sign in to start a discussion

Start a conversation about this story and keep it linked here.

Other hot threads

E-sports and Gaming Community in Kenya

Active 9 months ago

The Role of Technology in Modern Agriculture (AgriTech)

Active 9 months ago

Popular Recreational Activities Across Counties

Active 9 months ago

Investing in Youth Sports Development Programs

Active 9 months ago

Key figures and persons of interest featured in this article