We're loading the full news article for you. This includes the article content, images, author information, and related articles.

Ugandan President Yoweri Museveni’s recent calls for deeper East African integration, underscored by warnings of future conflict over sea access, have reignited debate on the future of the Kenya-Uganda border, a critical artery for regional trade and a historic flashpoint.

Ugandan President Yoweri Museveni has intensified his long-standing campaign for East African integration, urging the region’s youth to champion a political federation and questioning the logic of colonial-era borders that leave nations like his landlocked. Speaking at media engagements in Mbale, eastern Uganda, on Friday, November 14, 2025, Museveni argued that economic survival and prosperity are intrinsically linked to market integration, pointing to Uganda's production surpluses as a key driver for removing trade barriers.

His remarks, however, have stirred significant debate in Kenya, particularly after he framed access to the Indian Ocean as a fundamental right for landlocked states, warning that failure to guarantee it could lead to future wars. “How can you say that you are in a block of flats and the compound belongs only to the ground floor? That compound belongs to the whole block,” Museveni stated, metaphorically asserting Uganda's stake in the sea. These comments, delivered while outlining the seven pillars of his NRM party's 2026–2031 manifesto, which includes the Political Federation of East Africa, were interpreted by some analysts as a veiled threat towards Kenya, Uganda's primary corridor to global markets.

At the core of Museveni's argument is an economic imperative. He highlighted that Uganda produces 5.3 billion litres of milk annually but has a domestic demand of only 800 million litres. “We have a surplus of four billion litres. Sometimes Kenya buys, sometimes it doesn't, then we look to Algeria. It's the same issue with sugar, maize, cement,” he explained, stressing the need for a larger, guaranteed regional market.

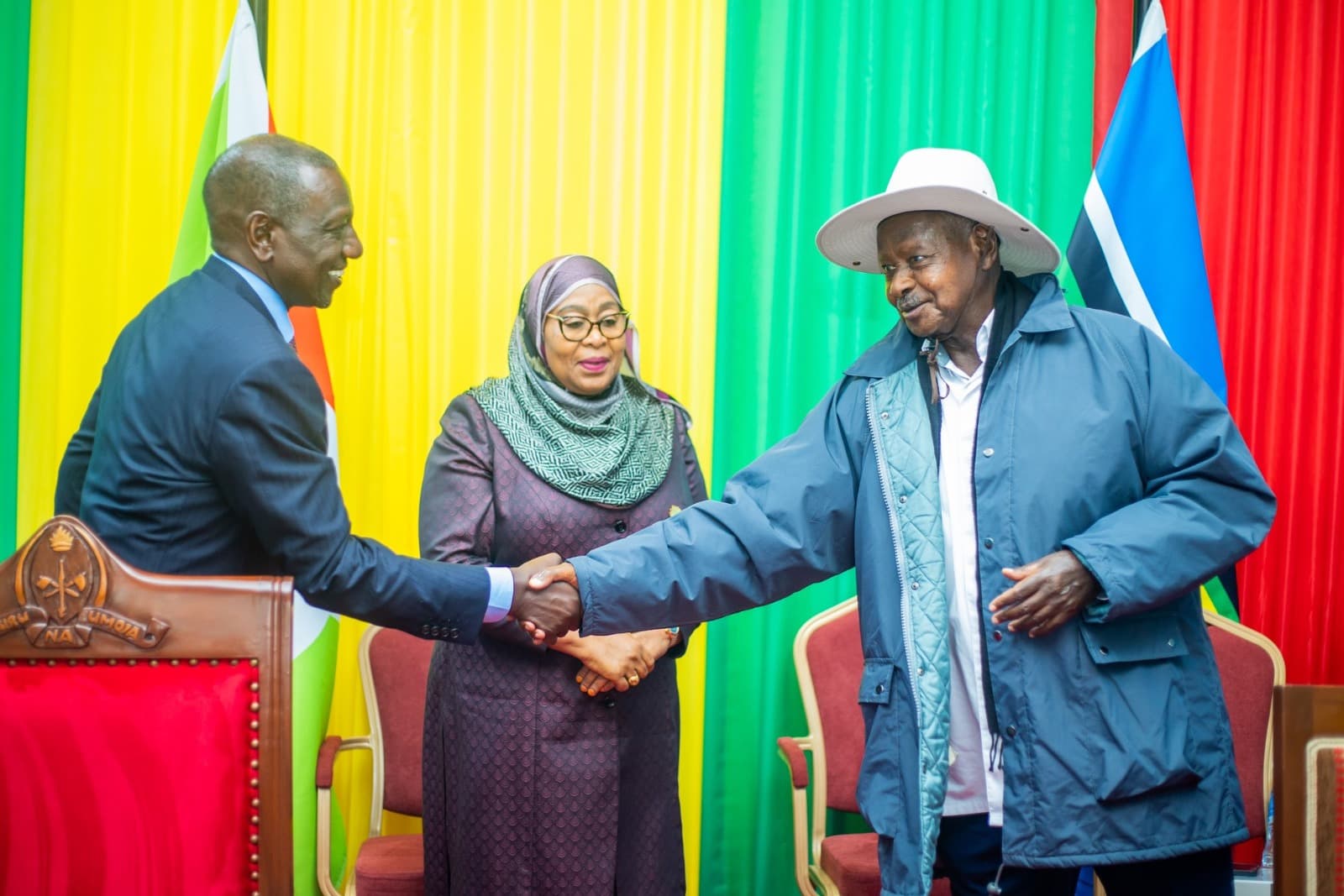

The push for a 'borderless' region is not a new phenomenon. In October 2022, Kenyan President William Ruto, during Uganda's 60th Independence Day celebrations, called on President Museveni to lead the charge in creating a “borderless East African Community.” “It is our place as leaders and citizens of the East African Region to work together so that we can transform our borders which today stand as barriers and convert them into bridges,” Ruto said at the time.

Despite this shared vision at the leadership level, the relationship between the two nations has a complex history marked by both cooperation and conflict. The East African Community (EAC), first established in 1967 and revived in 2000, stands as a testament to the collaborative spirit. However, historical tensions have occasionally flared, notably the border conflict between 1987 and 1990, fueled by mutual suspicion between the governments of Daniel arap Moi and Museveni. More recently, the unresolved dispute over the ownership of the fish-rich Migingo Island in Lake Victoria remains a persistent source of friction.

Away from the political rhetoric, tangible steps are being taken to ease cross-border movement and trade. In a significant move on August 30, 2025, trade ministers from both countries met in Mbale and agreed to eliminate all non-tariff barriers that hinder trade. The agreement followed a directive from Presidents Ruto and Museveni to resolve long-standing impediments and decongest the crucial Malaba and Busia border crossings.

These efforts build on the success of One-Stop Border Posts (OSBPs), such as the one in Busia, which was launched by both heads of state in 2018. According to TradeMark Africa, the OSBP has reduced the average time to cross the Busia border by as much as 84%, facilitating smoother trade for both large-scale cargo and the thousands of small-scale traders, many of whom are women, who depend on this route for their livelihoods. The volume of informal cross-border trade between the two nations is substantial, forming a critical economic lifeline for border communities.

For Kenya, the implications of a more integrated, or even borderless, relationship with Uganda are profound. Uganda is Kenya's most significant export market in the region. A seamless border would accelerate trade, reduce costs for consumers, and create new opportunities for Kenyan businesses. The tourism sector also stands to gain, with joint marketing initiatives already showing success as relaxed border restrictions have nearly doubled the flow of tourists between the two countries since 2022.

Kenya’s official response to Museveni's latest remarks has been measured. Foreign Affairs Principal Secretary Korir Sing'oei downplayed any diplomatic tensions, stating on November 12 that relations remain “steadfast and cordial.” This diplomatic calm suggests a recognition that while the high-level political discourse pushes for ambitious integration, the practical, economic realities of interdependence continue to drive cooperation on the ground. The challenge remains to reconcile the bold vision of a borderless East Africa with the historical sensitivities and security concerns that have long defined the relationship. FURTHER INVESTIGATION REQUIRED into the specific mechanisms for resolving historical disputes like Migingo Island in the context of deeper integration.

Keep the conversation in one place—threads here stay linked to the story and in the forums.

Sign in to start a discussion

Start a conversation about this story and keep it linked here.

Other hot threads

E-sports and Gaming Community in Kenya

Active 9 months ago

The Role of Technology in Modern Agriculture (AgriTech)

Active 9 months ago

Popular Recreational Activities Across Counties

Active 9 months ago

Investing in Youth Sports Development Programs

Active 9 months ago