We're loading the full news article for you. This includes the article content, images, author information, and related articles.

A growing trend of Cabinet Secretaries snubbing parliamentary committees is eroding legislative oversight, with analysts and lawmakers now arguing that MPs' own political compromises and failure to enforce sanctions are crippling accountability in Kenya.

NAIROBI, KENYA – A troubling pattern of Cabinet Secretaries (CSs) failing to honour summonses from parliamentary committees is threatening the constitutional authority of the Legislature, with a rising chorus of critics, including MPs themselves, now asserting that Parliament is complicit in its own diminishing power. This trend, described by lawmakers as “contempt of Parliament,” raises critical questions about the separation of powers and the effectiveness of oversight mechanisms designed to hold the Executive accountable to the Kenyan people.

The issue was recently highlighted in August 2025, when the Public Investments Committee on Commercial Affairs and Energy threatened to initiate impeachment proceedings against Treasury Cabinet Secretary John Mbadi and his Principal Secretary, Chris Kiptoo. The two officials were accused of persistently disregarding committee summonses to provide details on critical energy projects, including a stalled rural electrification programme worth Sh30 billion. Committee chairperson and Pokot South MP David Pkosing stated that the National Treasury was undermining Parliament and that such actions would not be taken lightly, calling impeachment a viable option.

This is not an isolated incident. Senators have also voiced frustration over CSs routinely ignoring invitations, sending last-minute apologies, or being selective about which summonses to honour. In June 2024, Senate Deputy Speaker Kathuri Murungi described the “flimsy reasons” given by ministers for non-appearance as “disrespectful and unacceptable.” This consistent defiance delays investigations, stalls reports, and ultimately weakens Parliament's ability to scrutinize government expenditure and policy implementation.

While it is easy to point fingers at an overreaching Executive, some political analysts and commentators argue the blame lies squarely with the lawmakers. According to this view, MPs have created a permissive environment for impunity through their own actions. One commentator, Taabu Tele, noted that Parliament “can’t eat its cake and have it,” suggesting that by vetting and approving overtly political appointees to the Cabinet, in potential violation of the spirit of the 2010 Constitution, MPs have weakened their moral and political authority to demand accountability.

Political partisanship is another significant factor. Observers note that MPs affiliated with the ruling coalition are often hesitant to rigorously question or sanction Cabinet Secretaries appointed by their party leader. This dynamic transforms critical oversight sessions into forums for political protection rather than genuine scrutiny, emboldening ministers to disregard summonses without fear of serious repercussions.

Furthermore, parliamentary monitoring organization Mzalendo Trust has raised concerns about Parliament's general responsiveness to public interests, citing absenteeism and a failure to align legislative work with citizens' needs. In its 2024 Parliamentary Scorecard, Mzalendo noted that a legislature struggling with internal challenges may find it difficult to project strength and enforce its mandate externally.

The Constitution of Kenya 2010, under Article 125, grants both Houses of Parliament and their committees the power to summon any person to give evidence or provide information. These powers are equivalent to those of the High Court and include the ability to enforce attendance of witnesses, examine them under oath, and compel the production of documents.

The Parliamentary Powers and Privileges Act, 2017, further operationalizes these powers. The Act empowers House committees to impose fines of up to KSh 500,000 on witnesses who fail to appear when summoned. The House also has the authority to order the arrest of a person who fails to honour a summons. Despite these legal provisions, committees rarely use these punitive measures, opting instead for public condemnations or threats that often go unfulfilled. This reluctance to act decisively has created a perception of Parliament as a toothless bulldog.

National Assembly Speaker Moses Wetang'ula has recently taken a firm public stance, announcing in November 2025 that he would summon Interior CS Kipchumba Murkomen to explain delays in the issuance of National IDs in Northern Kenya. He insisted that CSs must be held to account. However, critics argue that such summonses will only be effective if backed by a credible threat of sanctions as provided for in law.

The persistent disregard for parliamentary summons is more than just a procedural issue; it strikes at the heart of Kenya's democratic governance. Effective legislative oversight is a cornerstone of accountability, ensuring that the Executive branch is answerable to the people's representatives for its decisions and use of public funds. When Cabinet Secretaries can ignore Parliament without consequence, this vital check on power is nullified.

This erosion of authority could lead to reduced transparency in government operations, mismanagement of public resources, and a weakening of democratic institutions. For the Kenyan public, it means that critical questions about service delivery, from the issuance of identity cards to the implementation of multi-billion shilling development projects, may go unanswered, fostering a climate of impunity and diminishing public trust in both the Executive and the Legislature.

Keep the conversation in one place—threads here stay linked to the story and in the forums.

Sign in to start a discussion

Start a conversation about this story and keep it linked here.

Other hot threads

E-sports and Gaming Community in Kenya

Active 9 months ago

The Role of Technology in Modern Agriculture (AgriTech)

Active 9 months ago

Popular Recreational Activities Across Counties

Active 9 months ago

Investing in Youth Sports Development Programs

Active 9 months ago

Key figures and persons of interest featured in this article

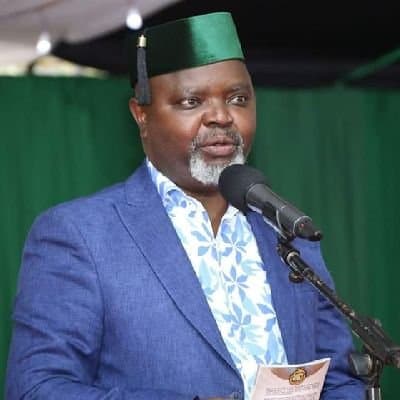

Cabinet Secretary for the Interior and National Administration

Senator for Meru County

Member of Parliament, Pokot South

Cabinet Secretary for National Treasury and Economic Planning