We're loading the full news article for you. This includes the article content, images, author information, and related articles.

Whether Mount Kenya leaders can rise above personal ambition and present a cohesive front—or continue down the path of fragmentation—will not only shape the region’s destiny but also profoundly affect the outcome of Kenya’s next political chapter.

The Mount Kenya region, long regarded as the fulcrum of Kenya’s political arithmetic, is facing an unprecedented test of unity. Traditionally viewed as a cohesive voting bloc capable of swinging presidential elections, the region is now grappling with internal divisions, competing loyalties, and a fast-evolving national landscape that is straining its once-monolithic political identity.

As national alliances fracture and new power centers emerge, leaders from the agriculturally rich and electorally potent counties of Kiambu, Nyeri, Murang’a, Kirinyaga, Meru, and Embu are under pressure to either consolidate regional influence or risk irrelevance. The question now is not just whether Mount Kenya can speak with one voice—but whether that voice still carries the same political weight it once did.

For two decades, the region enjoyed unparalleled political clout, first under President Mwai Kibaki and later as the home base of President Uhuru Kenyatta. During this period, the region often voted overwhelmingly as a unit and enjoyed significant access to the levers of power.

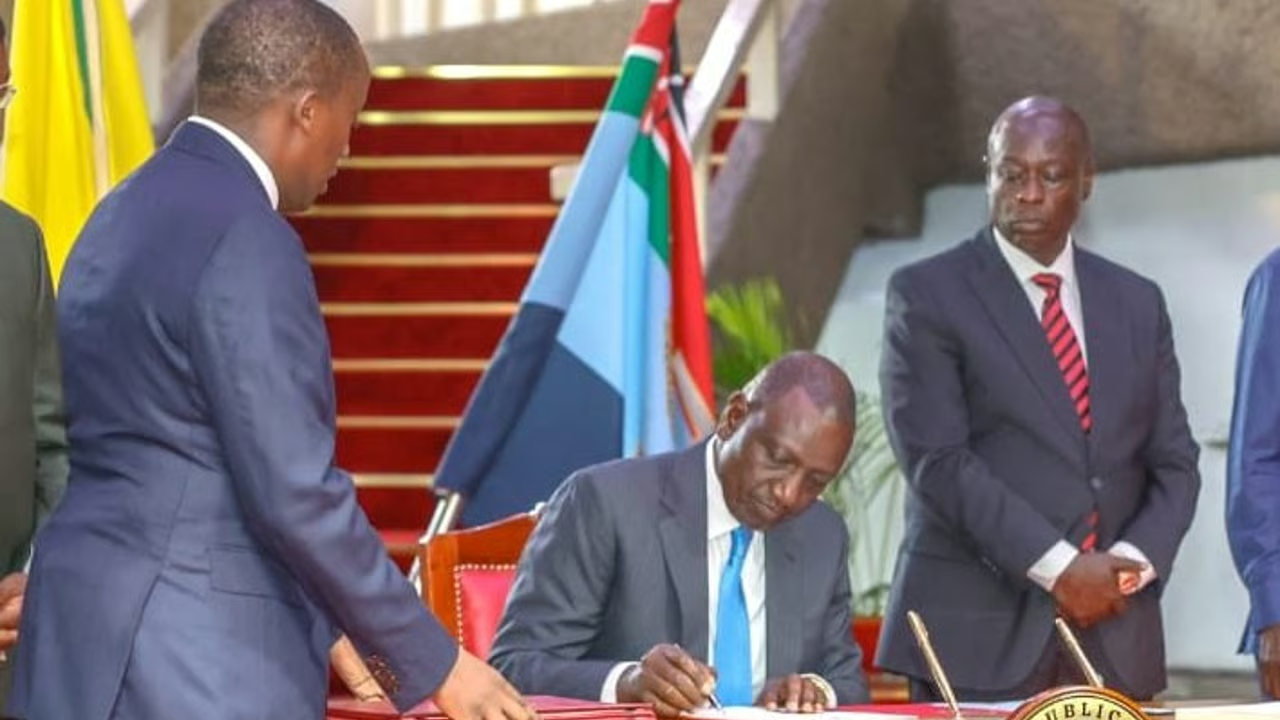

But the post-Uhuru era has ushered in a new and more volatile chapter. Despite supporting President William Ruto’s 2022 State House bid in large numbers, Mount Kenya has since grown increasingly restless within the Kenya Kwanza coalition. A segment of the electorate—and some elected leaders—believe the region is not getting its fair share of appointments, development projects, or political recognition.

“We are not beggars in this government,” Nyeri Senator Wahome Wamatinga declared recently. “We delivered votes, and we expect respect, not neglect.”

At the same time, younger leaders such as Kiharu MP Ndindi Nyoro and Kirinyaga Governor Anne Waiguru are positioning themselves as national players—often with divergent strategies—while veteran figures like former Agriculture CS Mwangi Kiunjuri and Narc-Kenya leader Martha Karua continue to push for regional realignment outside the ruling coalition.

A key factor behind the emerging cracks is the absence of a singular figure able to unify the diverse counties under a common political agenda. While President Kenyatta once played that role, his retirement—and subsequent detachment from active politics—has left a vacuum. Efforts to fill it have so far faltered amid factionalism and ambition.

Governor Waiguru has courted national visibility through her role as Chairperson of the Council of Governors. MP Ndindi Nyoro, a close ally of President Ruto, is seen by some as the heir apparent to central Kenya’s political throne. Yet both face resistance from peers wary of their growing influence.

“There is no consensus on leadership,” says political analyst Herman Manyora. “Mount Kenya now has multiple centers of gravity, and that weakens its bargaining power.”

This fragmentation was starkly visible during recent national protests, where leaders from the region took contrasting stances—some defending government action, others voicing concern over youth disenfranchisement and economic exclusion.

Beyond the leadership wrangles, deeper socio-economic frustrations are brewing. The cost of living, especially rising food and fuel prices, has eroded public confidence. Coffee and tea farmers complain of delayed payments and market manipulation, while youth unemployment remains high despite campaign promises.

These conditions have sparked growing street-level disillusionment, particularly among the youth in urban centers like Thika, Nyeri, and Murang’a. Protest turnout and online dissent in the region have grown markedly, challenging the assumption that Mount Kenya remains a political fortress for the ruling party.

“The narrative is shifting,” says Pauline Njoroge, a vocal political strategist. “People are asking hard questions about what they voted for versus what they’re living through.”

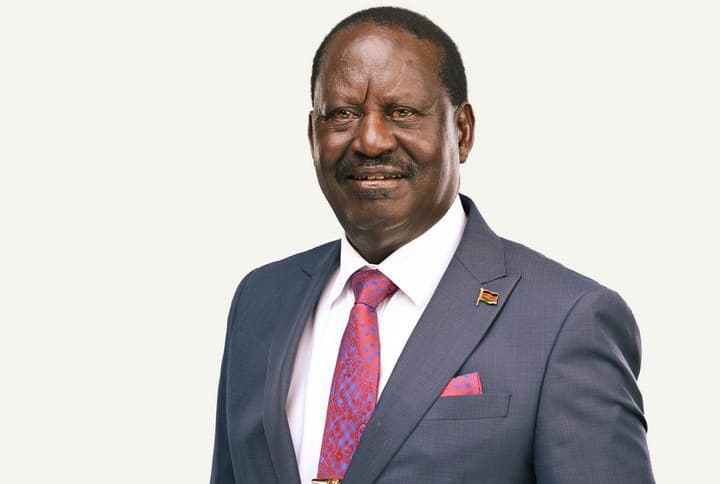

Meanwhile, overtures by Azimio la Umoja leader Raila Odinga toward reconciliation and constitutional reform have found new, if cautious, ears in the region—especially among moderate and disillusioned leaders. Odinga’s pan-Kenyan appeal, bolstered by his diplomatic engagements and anti-corruption messaging, is slowly gaining traction even in areas that once viewed him with deep suspicion.

Whether this can translate into electoral gains remains uncertain, but it signals a potential recalibration ahead of the 2027 general election.

At the same time, the prospect of a Gachagua-Ruto rivalry within Kenya Kwanza—fueled by perceptions of marginalization—could split the regional vote. Deputy President Rigathi Gachagua continues to position himself as the region’s defender, but critics accuse him of playing ethnic politics rather than national statesmanship.

Mount Kenya’s political future is far from settled. Without a unifying figure, a clear economic recovery strategy, or a shared regional vision, its influence risks diminishing at the national table. Yet, the region remains too populous, too economically vital, and too politically experienced to be written off.

Whether Mount Kenya leaders can rise above personal ambition and present a cohesive front—or continue down the path of fragmentation—will not only shape the region’s destiny but also profoundly affect the outcome of Kenya’s next political chapter.

As alliances shift and voter sentiments evolve, the question facing Mount Kenya is no longer just who leads, but what unites.

Keep the conversation in one place—threads here stay linked to the story and in the forums.

Other hot threads

E-sports and Gaming Community in Kenya

Active 8 months ago

The Role of Technology in Modern Agriculture (AgriTech)

Active 8 months ago

Popular Recreational Activities Across Counties

Active 8 months ago

Investing in Youth Sports Development Programs

Active 8 months ago

Key figures and persons of interest featured in this article

Deputy President of Kenya (2022–2024)

Senator for Nyeri County

Leader of the Opposition

Kiharu MP & Chair of Budget and Appropriations Committee

Party Leader, NARC-Kenya

3rd President of Kenya (2002–2013)