We're loading the full news article for you. This includes the article content, images, author information, and related articles.

A comparative analysis of Abia State’s governance turnaround under Governor Alex Otti, offering a blueprint for Kenyan counties on defeating political patronage.

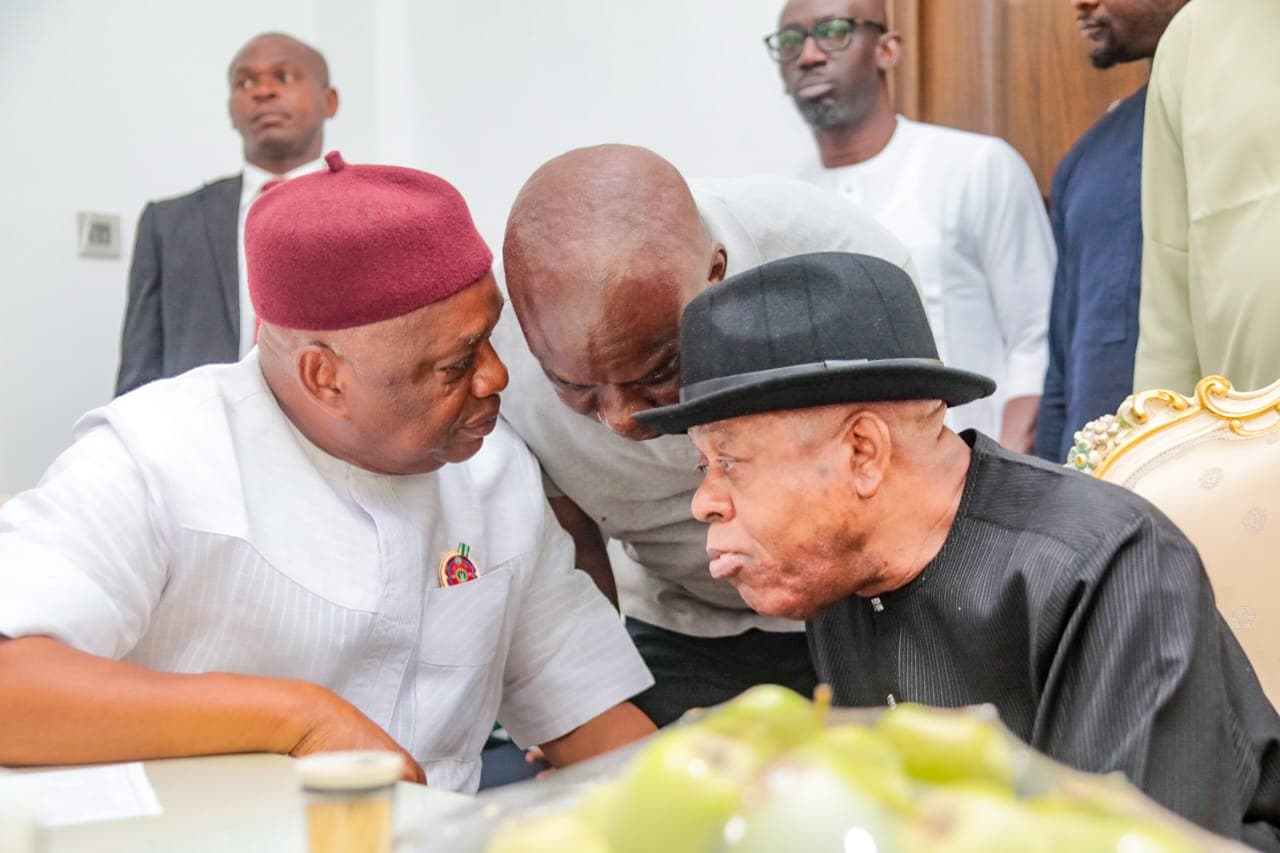

In the often-chaotic theatre of Nigerian politics, Abia State has become an unexpected case study in how competence dismantles entrenched political cartels. Under Governor Alex Otti, a former banker with no roots in traditional godfather networks, the state is undergoing a transformation that challenges long-held assumptions about African politics: that power must be ritualised, patronage-driven, and ethnically negotiated to survive.

Writing recently, Nigerian public intellectual Chidi Amuta made a bold but defensible claim — that the 2027 Abia governorship contest is effectively settled. Not because of propaganda or incumbency muscle, but because performance has replaced political mysticism as the organising principle of power.

For decades, Abia was synonymous with what Amuta describes as political witchcraft:

godfathers who anointed successors,

opaque financial systems,

unpaid salaries,

and a capital city that decayed in plain sight.

Otti’s administration has disrupted that ecosystem in the most dangerous way possible for cartels: by making government work.

Civil servants are paid on time.

Long-abandoned roads are being reconstructed.

And Aba, long celebrated as the “Japan of Africa” for its manufacturing ingenuity, is regaining commercial energy through infrastructure upgrades and regulatory order.

This is not rhetorical governance. It is visible, measurable, and politically lethal to those who thrived on chaos.

Otti’s greatest political sin is not ideology — it is proof.

Proof that:

you can govern without looting,

you can win loyalty without ethnic mobilisation,

and you can secure political survival without blessing from political shrines.

In patronage systems, failure is profitable.

In performance systems, failure is terminal.

That is why, as Amuta argues, the old political order in Abia is not merely losing relevance — it is facing extinction. Once voters experience functional governance, regression becomes politically unacceptable.

For Kenya’s governors — especially those presiding over restive, debt-strained counties — Abia offers a sobering lesson.

Kenyan politics often assumes:

tribal arithmetic guarantees re-election,

visibility matters more than delivery,

and succession can be manufactured.

Abia is demonstrating the opposite.

Delivery is becoming the strongest ethnic identity.

Roads, salaries, healthcare, and order are outperforming clan mobilisation and elite endorsements.

In devolved systems, where governors are closer to the voter than presidents, this lesson is especially sharp: competence scales faster than propaganda.

Perhaps the most disruptive implication of Otti’s success is this:

the era of the anointed successor is collapsing.

When governance becomes tangible, voters stop asking “Who sent you?” and start asking “What have you done?” That shift is existentially dangerous for political machines built on inheritance rather than impact.

In Abia, the train has left the station.

Those standing on the tracks — the political witches, godfathers, and custodians of decay — are discovering that progress is not negotiable. It does not pause for nostalgia. It does not respect old spells.

And for Kenya, watching closely, the message is unmistakable:

in the age of devolution, competence is not just good governance — it is political survival.

Keep the conversation in one place—threads here stay linked to the story and in the forums.

Sign in to start a discussion

Start a conversation about this story and keep it linked here.

Other hot threads

E-sports and Gaming Community in Kenya

Active 9 months ago

The Role of Technology in Modern Agriculture (AgriTech)

Active 9 months ago

Popular Recreational Activities Across Counties

Active 9 months ago

Investing in Youth Sports Development Programs

Active 9 months ago