We're loading the full news article for you. This includes the article content, images, author information, and related articles.

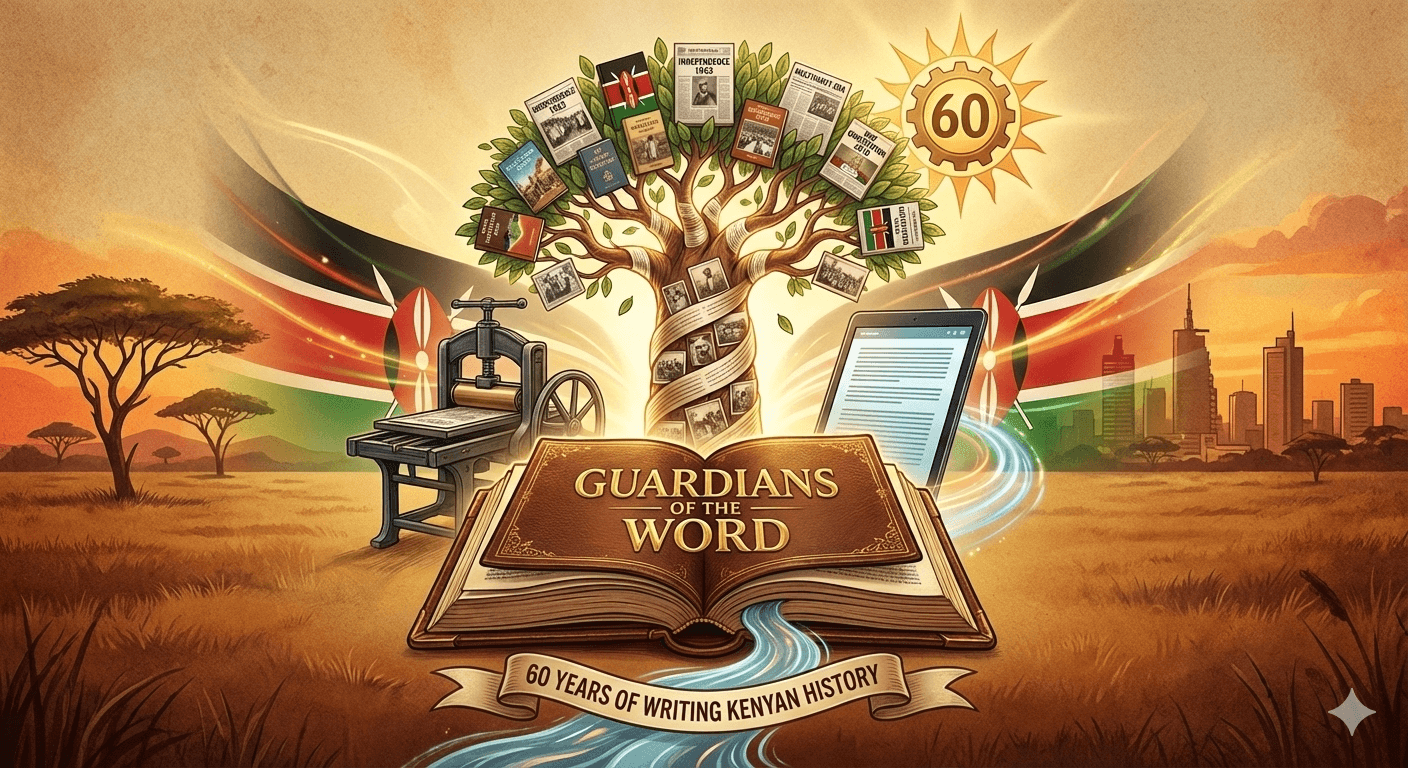

From a colonial outpost to a powerhouse of indigenous thought, East African Educational Publishers celebrates six decades of defying silence and shaping the African narrative.

It began with a simple, radical idea: that African stories should be told by African voices, on African paper, owned by African people. Today, as East African Educational Publishers (EAEP) marks its 60th anniversary, the orange spines of its books line the shelves of millions of Kenyan homes—silent witnesses to a nation’s intellectual coming of age.

For six decades, this Nairobi-based institution has done more than print textbooks; it has curated the soul of a continent. From the fiery prose of Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o to the satirical bite of Francis Imbuga, EAEP has been the engine room of African literature, surviving censorship, economic turbulence, and the digital revolution.

Founded in 1965 as a local branch of the British firm Heinemann, the company was initially an outpost for colonial commerce. But the script flipped in 1972 with the arrival of Henry Chakava, a young, bold editor who would later become the father of Kenyan publishing.

Chakava, who passed away in 2024, didn’t just run a business; he fought a cultural war. In 1992, he led a group of local investors to buy out the British owners, transforming Heinemann Kenya into the fully indigenous EAEP. It was a move that stunned the global publishing world—a David buying out Goliath’s local franchise.

The stakes were often higher than profit margins. In the 1980s and 90s, publishing in Kenya was a dangerous trade. When Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o decided to abandon English for Gikuyu to "decolonize the mind," international publishers balked. They saw no market; Chakava saw a moral imperative.

"He risked his life and livelihood to give voice to the silenced," notes literary scholar Godwin Siundu. By publishing works like Decolonising the Mind and Matigari, EAEP didn't just sell books; they challenged the Moi regime’s grip on truth. At one point, intelligence officers famously raided bookshops looking for the fictional character Matigari, assuming he was a real dissident.

For the average Kenyan, however, EAEP’s impact is felt most in the classroom. If you went to school in East Africa, you likely grew up on a diet of their "set books." Titles like Betrayal in the City and The River Between are not just literature; they are rites of passage.

This dominance has economic weight. With the average set book retailing between KES 600 and KES 1,200, the publisher has navigated the delicate balance of affordability versus sustainability. In an era where parents grapple with the cost of the Competency-Based Curriculum (CBC), EAEP’s role in keeping knowledge accessible remains critical.

"A nation that does not read its own stories is a nation without a mirror," Chakava once said. As EAEP steps into its seventh decade, it faces new giants: TikTok attention spans, piracy, and the rising cost of paper. Yet, its legacy is secure. It proved that African literature is not a charity case for Western publishers, but a vibrant, viable, and necessary industry of its own.

Keep the conversation in one place—threads here stay linked to the story and in the forums.

Sign in to start a discussion

Start a conversation about this story and keep it linked here.

Other hot threads

E-sports and Gaming Community in Kenya

Active 9 months ago

The Role of Technology in Modern Agriculture (AgriTech)

Active 9 months ago

Popular Recreational Activities Across Counties

Active 9 months ago

Investing in Youth Sports Development Programs

Active 9 months ago