We're loading the full news article for you. This includes the article content, images, author information, and related articles.

A Turkish activist’s quest to uncover his origins reveals a painful, overlooked chapter of the Indian Ocean slave trade that reached deep into the Central Highlands.

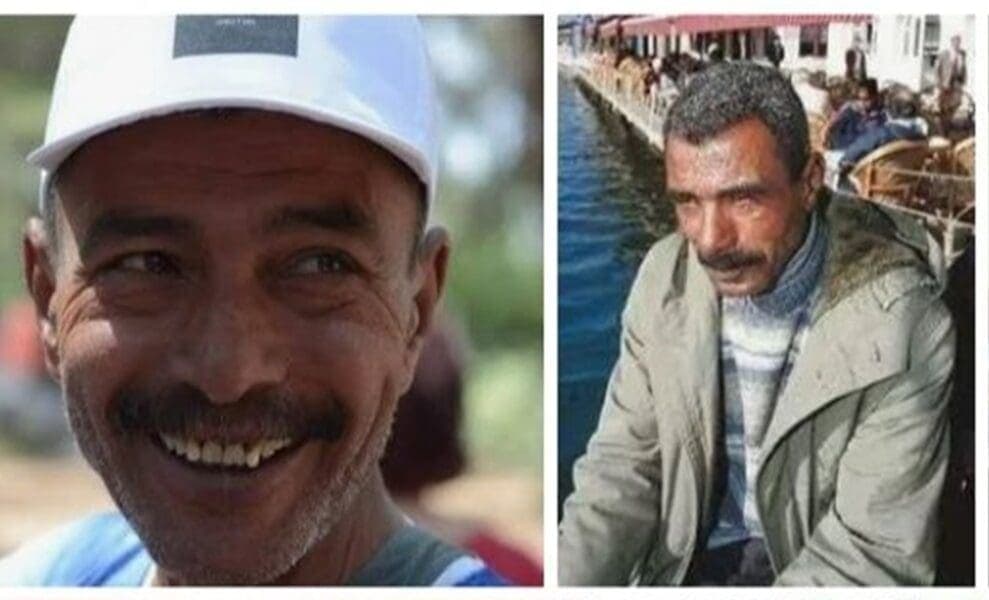

Mustafa Olpak grew up on Turkey’s Aegean coast, shrouded in a silence so heavy it felt like protection. For decades, the story of his family was a sanitized narrative of migration and loss—a tale of Muslims uprooted from Crete during the 1923 population exchange with Greece. But beneath the surface lay a secret his elders were terrified to touch.

It took a cryptic warning from an elderly relative to shatter the quiet: “Our people came from Africa, but that is a painful story. Leave it alone.”

Olpak did not leave it alone. Instead, his subsequent investigation has rewritten the boundaries of the East African slave trade, tracing his lineage not just to the Swahili coast, but shockingly, to the Kikuyu highlands of Central Kenya. His findings challenge the long-held assumption that the Indian Ocean trade was strictly a coastal affair, revealing a complex web that dragged highlanders from the ridges of Mount Kenya to the palaces of the Ottoman Empire.

Olpak, who passed away in 2016 after founding the Afro-Turk Association, became the first of his community to methodically document this history. His journey began in the dusty archives of Istanbul and Crete but inevitably pointed south toward the equator. By triangulating Ottoman household records with oral histories from Afro-Cretan families, Olpak unearthed a startling reality: his ancestors were not coastal Swahili, but Kikuyu people taken from the Kenyan interior in the late 19th century.

For Kenyans today, this connection is jarring. We are taught to associate the slave trade with the humidity of Mombasa, the dungeons of Fort Jesus, and the clove plantations of Zanzibar. The idea that a farmer from the misty slopes of the Aberdares could end up serving in an Ottoman household in Turkey seems geographically impossible.

Yet, historical records validate Olpak’s discovery. In the late 1800s, the trade routes were shifting.

The late Kenyan historian Bethwell Ogot, a titan of continental scholarship, famously described the slave trade as an “endlessly bleeding wound.” While the coast bore the brunt, the interior was not immune. In the 1870s and 1880s, driven by an insatiable global demand for ivory, Swahili-Arab caravans pushed deeper inland.

These caravans did not just carry tusks; they carried people. Historical analysis suggests several factors made the highlands vulnerable during this period:

Olpak believed his ancestors were seized during one of these violent intersections. They would have been chained into coffles for a brutal march lasting weeks, descending from the cool highlands to the scorching heat of coastal entrepôts like Mombasa or Bagamoyo.

Once at the coast, the captives entered a global machine. Tanzanian historian Abdul Sheriff, a leading authority on the Indian Ocean world, has spent decades documenting how this system tied East Africa to Arabia, Persia, and the Ottoman Empire. Unlike the Atlantic trade, which focused on plantation labor in the Americas, the Indian Ocean trade often fed domestic servitude and military roles in the Middle East and Turkey.

Mauritian historian Vijayalakshmi Teelock notes that tens of thousands of East Africans were absorbed into this diaspora. For Olpak’s ancestors, the journey involved crossing the Indian Ocean, likely passing through the slave markets of Zanzibar, before being sold into servitude in Crete—then an Ottoman province.

When the Ottoman Empire collapsed and the Turkish Republic was formed, these Afro-Cretans were caught in the 1923 population exchange. They were moved to Turkey, not as Africans, but as “Muslims,” their true origins erased by bureaucracy and trauma.

Today, the Afro-Turk community numbers in the thousands, concentrated around Izmir. Thanks to Olpak’s work, they are beginning to reclaim a history that spans continents. For Kenya, the story serves as a somber reminder: our history is not contained within our borders. The ridges of Kirinyaga and the shores of the Aegean are linked by a lineage of survival, proving that even a century of silence cannot bury the truth.

Keep the conversation in one place—threads here stay linked to the story and in the forums.

Sign in to start a discussion

Start a conversation about this story and keep it linked here.

Other hot threads

E-sports and Gaming Community in Kenya

Active 9 months ago

The Role of Technology in Modern Agriculture (AgriTech)

Active 9 months ago

Popular Recreational Activities Across Counties

Active 9 months ago

Investing in Youth Sports Development Programs

Active 9 months ago